In Uganda’s Kasese district, Indigenous women are reviving floodplains with native trees and traditional knowledge

- Posted on October 15, 2025

- Latest News

- By Admin

- 259 Views

Frontline communities living at the foothills of the Rwenzori are turning to Indigenous knowledge in order to adapt to and mitigate recurring climate-induced floods.

By INNOCENT KIIZA-Kasese district, Uganda

In recent years, torrents of muddy water have torn through villages in Uganda’s Kasese district sweeping away homes, bridges, and farmland, uprooting entire communities. Kasese’s floods are a mirror of a nation caught between extreme weather events, struggling to adapt with scarce resources. Now, frontline communities living at the foothills of the Rwenzori are turning to Indigenous knowledge in order to adapt to and mitigate recurring climate-induced floods.

For Mbambu Syalivina, a mother of four, indigenous trees are both a defense and a heritage. After mudslides displaced her neighbors in the 2019 floods, she planted Markhamia lutea along the edges of her land. Today, their roots lock the soil together, shielding her family’s small farm from disaster.

“I learned from my mother, who was taught by her grandmother,” she says. “These trees not only protect us from disasters but also provide medicine.”

Her family also digs trenches in their gardens, another traditional practice passed down through generations. The ditches capture rainwater, slow runoff, and preserve soil moisture during long dry spells.

.jpg)

Masereka points to Markhamia lutea, a tree with strong roots that hold soil firm photo by Innocent kiiza.

Janet Nyakairu, 57, from the Banyabindi community, has a similar story. She was evicted from protected land which hosts part of Queen Elizabeth National Park. She bought two hectares of land nearby where she now grows coffee, beans, and vegetables. Around her home, Grevillea and Albizia coriaria trees stand tall.

“When the winds blow, my house and garden remain safe,” she says proudly. An agricultural officer once taught her to dig deep trenches 10 feet long, 2 feet wide to trap floodwater and prevent soil loss.

Nyakairu believes indigenous practices are not only cheaper but more sustainable as they are nature based.

“Tree leaves provide medicine, manure, and shade,” she explains. “They feed both the soil and the family.” However, she points out that women’s limited access to land has impeded some of the tree planting and conservation efforts. “We can’t plant or conserve without men’s approval,” she says.

Emmanuel Masereka, 65, is the coordinator of the Mbaihamia Healing Forest initiative, an indigenous-led initiative that creates and preserves indigenous trees and green spaces in Kasese.Standing near his farm, he recalls the devastation of 2019, when floods swept through his village.

.jpg)

Mbambu's garden is intercropped with Grevillea trees ,photo by Innocent Kiiza

His neighbors lost their homes, crops were destroyed, and many were forced into displacement camps. His own house nearly vanished under the force of the water.

“If we don’t return to our indigenous knowledge, we won’t survive,” Masereka says.For the last 5 years, he has been teaching his community how native trees could shield them against floods, strong winds, and mudslides.

He points to Markhamia lutea, a tree with deep taproots that hold soil firm while its leaves provide nectar for bees. Nearby stands Ficus natalensis locally known as omutoma, whose roots anchor the land against erosion and whose leaves serve as medicine and fodder for goats.

Mountain bamboo, with its interlocking web of roots, reinforces riverbanks providing natural fencing, while the umbrella-shaped dracaena channels water safely in one direction.

“These trees are more than plants,” Masereka explains. “They are shields, protecting our homes, farms, and our lives.”

Masereka interplants his trees with pumpkins whose broad leaves blanket the soil, preventing erosion while enriching fertility once decomposed. His valley home, once a danger zone, is now a haven even in heavy rains.

Muguma Evelyne, Environment Officer for Kasese Municipality, says women like Mbambu and Nyakairu are proof that indigenous knowledge can transform fragile landscapes.

.jpg)

“Rainfall patterns have changed in Kasese. Rains now come late, in short, violent bursts, causing floods even in places without rivers,” she explains. “Every rainy season, people come asking for indigenous seedlings not just to plant, but for learning purposes.” The municipality now runs nurseries that distribute native tree seedlings, with a focus on women.

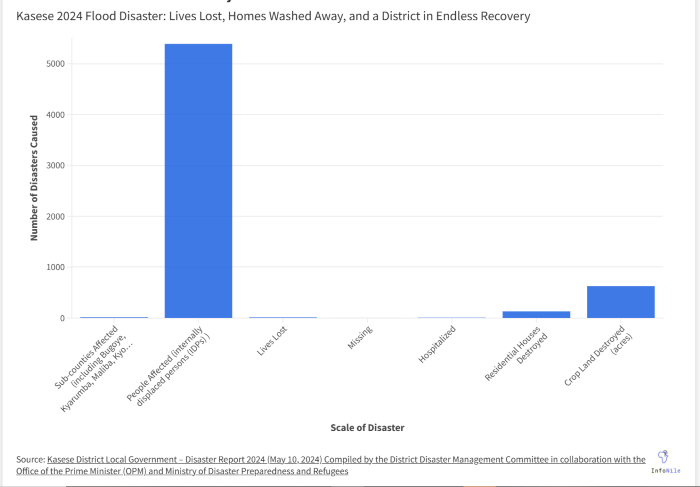

In May 2024, floods from the Rwenzori Mountains burst riverbanks, sweeping through villages in Bugoye, Kyarumba, and Maliba in Kasese District. Around 13 people lost their lives, and more than 5,389 residents were displaced as homes, schools, and farms were submerged. According to the Kasese District Disaster Report 2024, over 626 acres of farmland were destroyed, 130 houses were reduced to rubble, and ten major roads rendered impassable. The floods also washed away key bridges, including Lambert and Kabiri, cutting off access to essential services such as Isule Health Centre III.

source: infonile

Culture, Gender, and Conservation

The cultural role of trees is as important as their ecological value. In Bakonzo tradition, Dracaena trees mark family boundaries and prevent erosion, while the Ficus (Omutoma), planted at the heart of family land, symbolizes continuity and resilience.

“These trees are our identity,” Evelyne says. “They remind us that conservation is not just about the environment,it is also about culture and heritage.”

Willson Muwa Muhindo, deputy minister for land and agriculture production in Obusinga Bwa Rwenzururu Kingdom, commends women’s leadership in climate action. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Muhindo says, neighbors flocked to his home for herbal remedies, some even calling him a herbalist.

He warns against planting exotic species, which he says bring risks such as attracting lightning or displacing native biodiversity. “Use indigenous knowledge to guide decisions, to manage resources, and to teach young people why native trees matter for both culture and climate,” he pleads.

Indigenous Women’s Voices Missing at Global Platforms

Immaculate Kibaba, Programs Officer at the Center for Citizen Conservation of the Environment, says indigenous women’s voices remain marginalized in climate adaptation debates.

“Local indigenous women are left out of international platforms, even though they are the ones directly affected,” she says. “If Mbambu and Nyakairu could have the opportunity to share their lived experiences and knowledge at COP30 in Brazil, the world would benefit greatly from their stories.”

She recalls the devastating 2013 floods in Kasese that swept away farms, homes, and lives. In response, communities turned to agroforestry and intercropping on the Rwenzori slopes.

Today, land once bare has been replanted with Grevillea, Markhamia lutea, Leucaena leucocephala, Dracaena fragrans, Guava, Berries, pawpaw, and Calliandra calothyrsus. These trees not only stabilize soils and control floods, but also provide food, medicine, and nitrogen-rich manure.

“Fertilizers degrade soil and release carbon emissions,” Kibuuba argues. “But indigenous methods like mulching, trenching, intercropping—restore fertility naturally and help rainfall cycles recover.” She urges policymakers to consult indigenous communities before drafting agricultural policies. “Too often, decisions prioritize profits over people and nature,” she says.

A Global Perspective

According to Niklas Hagelberg, Senior Programme Coordinator for Climate Action at the United Nations, indigenous knowledge is essential for ecosystem management.

“There is no single solution to climate change but climate-smart ecosystem management, including the use of indigenous trees delivers both mitigation and adaptation,” he says.

Hagelberg is keen to emphasize that native species are better suited to withstand climatic extremes but long-term care of planting sites is critical for these trees to thrive.“If Uganda invests in scaling up indigenous knowledge, the Rwenzori foothills may not just endure the storms ahead, but flourish because of them,” he said.

Write a Response